On June 8, 1964, Gerald Gault and Ronald Lewis were arrested when their neighbor, Mrs. Cook, alleged they had made a lewd phone call to her home. The police detained Gerald overnight and held a hearing the next day in the juvenile judge’s chambers. Gerald’s parents, who were at work at the time of his arrest, were not notified, and Gerald was not provided an attorney during his interrogation or at either of his two hearings. Gerald was found to be guilty of an Arizona statute that makes it a crime to use “vulgar, abusive or obscene language in the presence of a woman or a child,” and was committed to the Arizona State Industrial School until his 21st birthday. Gerald was 15 at the time of his arrest.

By the time the U.S. Supreme Court heard his case, In re Gault, on December 6, 1966, Gerald had been living in detention for two and a half years.

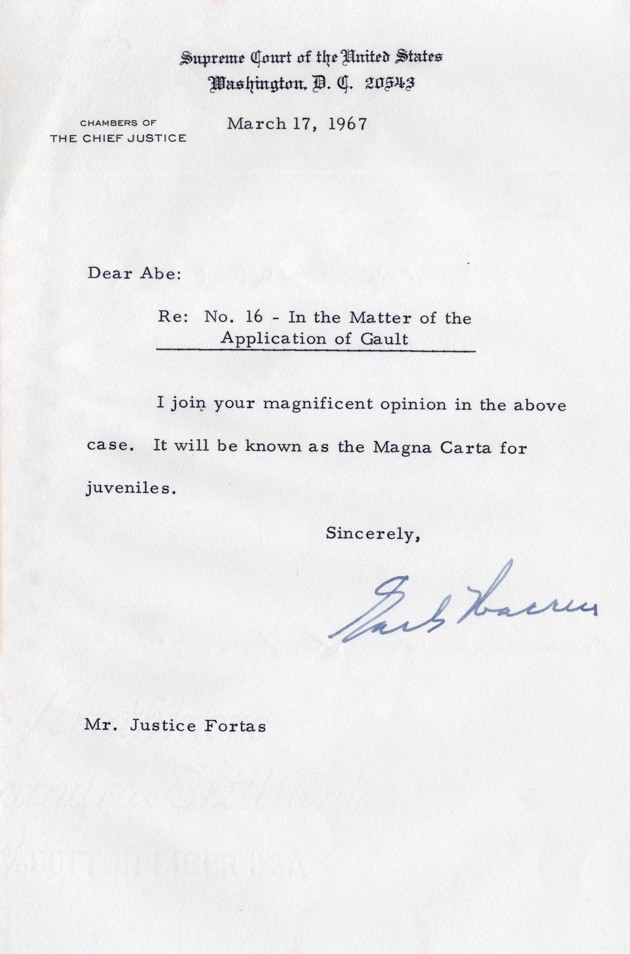

On May 15, 1967, the Supreme Court ruled that the state of Arizona violated Gault’s due-process rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, and that Constitutional due-process rights apply to children as well as to adults. Justice Abe Fortas’s majority opinion, dubbed “the Magna Carta for juveniles” by Chief Justice Earl Warren, stated that even in the case of juveniles, “Due process of law is the primary and indispensable foundation of individual freedom.”

uvenile courts have historically functioned under the ethos of parens patriae, the assumption that courts acts in the best interest of those who cannot help themselves. As a result, the juvenile-court system operates according to a parental rather than adversarial process, an informal, ad hoc judicial process governed by a supposedly benevolent and paternal juvenile court. In Justice Fortas’s opinion, this improvisational, parens patriae practice, no matter how well-intentioned, is the enemy of justice and individual rights. “[U]nbridled discretion, however benevolently motivated, is frequently a poor substitute for principle and procedure,” and “departures from established principles of due process have frequently resulted not in enlightened procedure, but in arbitrariness,” Fortas wrote.

The primary holding in Gault is that children have the right to legal representation during the judicial process, and that proper procedure, not discretion, is necessary to ensure this right. “The juvenile needs the assistance of counsel to cope with problems of law, to make skilled inquiry into the facts, to insist upon regularity of the proceedings, and to ascertain whether he has a defense and to prepare and submit it. The child ‘requires the guiding hand of counsel at every step in the proceedings against him,’” Fortas wrote in his majority opinion, quoting Kent v. United States.

This year, the 50th anniversary of In re Gault, the National Juvenile Defender Center (NJDC) sought to determine just how successful the Gault decision has been in protecting the due-process rights, and specifically access to legal counsel, of the more than 1 million children who enter the American court system each year. Their findings, detailed in the report, “Access Denied: A National Snapshot of States’ Failure to Protect Children’s Right to Counsel,” suggest that the majority of states fail to protect children’s right to counsel, either in law or practice, in five significant ways.

Right to counsel regardless of financial status is guaranteed under the U.S. Constitution, and yet children are not automatically presumed to be eligible for free legal representation. Children’s eligibility is often predicated on an investigation of the family’s financial status, and this can significantly delay access to counsel while children await assistance in detention. The financial-qualification process can result in disagreements over the need for counsel. Mary Ann Scali, the executive director of the NJDC, says that Gault establishes “the child’s right to a lawyer, not the family’s right to a lawyer.”

Even in states where children are guaranteed counsel, access to an attorney may not be triggered early enough in the judicial process. Many children face interrogation without the guidance of counsel, for no U.S. state specifically provides children with access to counsel during interrogation, and only Illinois has provisions, albeit limited ones, to ensure that children younger than 15 who have been accused of “serious” offenses are provided with counsel during interrogation. The need for representation during interrogation, and the underlying power imbalance between children and law enforcement, is illustrated in the “Access Denied” report via a quote from Haley v. Ohio:

A 15-year-old lad, questioned through the dead of night by relays of police, is a ready victim of the inquisition. Mature men possibly might stand the ordeal from midnight to 5 a.m. But we cannot believe that a lad of tender years is a match for the police in such a contest. He needs counsel and support if he is not to become the victim first of fear, then of panic.

When children are kept under arrest, interrogated over long periods of time, and not allowed to leave police custody, they are vulnerable to abuses in the system. The Gault decision applies to, as Fortas wrote, “every step of the proceedings.” Scali points to this underlying imbalance of power in the interrogation phase of the judicial process, arguing, “The idea that children should face interrogation without a lawyer really cuts against everything we know about child coercion, and children’s susceptibility to make a confession.”

The right to a lawyer, even when a child cannot afford one, is an essential element of due process, but in 36 states, even children who qualify for “free” counsel are expected to pay for that representation after the fact, often in the form of administrative and case fees. These fees range from $10 to over $750 depending on the state, the severity of the charges, or the fee in question. What’s more, nine states charge fees in exchange for the administrative burden of discovering whether a family can afford court fees in the first place.

Children deemed eligible for legal counsel may choose to waive that right, but the NJDC argues that minors should be provided with counsel immediately upon arrest so they can make an informed, thoughtful decision to waive their rights. Forty-three states allow children to waive this right before actually speaking with a lawyer about the services they are waiving. Scali said, “In many cases children are being asked by a judge, ‘Do you want a lawyer here today or should we just move forward?’ Our recommendation is let’s make sure the person having the conversation [about waiving right to counsel] with the child is a lawyer, who can say, ‘I’m here for you, this is what could happen today. Let’s walk into court together and the judge will ask you whether or not you’d like my assistance.”

A lawyer provides vital counsel not just during the interrogation and hearing, but after the child has been sentenced, and may have no other advocate. Currently, only 11 states ensure children have access to an attorney while in detention, creating what one juvenile defender quoted in the “Access Denied” report calls a “legal moat” between the child and his counsel. “We sentence and incarcerate children at a higher rate than any other nation in the world times two, and yet we cut off their access to counsel in most states,” Scali said. Children are acutely vulnerable to abuses of power, rape, and isolation in detention, and denying these minors access to their lawyer only isolates them further from their only safeguard for personal safety and legal recourse.

Still, according to Kim Tandy, the executive director of the Children’s Law Center, Inc., and a consultant to the Indiana Public Defender Council, while many states fall short in their protections for juveniles, some are successfully executing the rights established by Gault.

We see a wide disparity in right to counsel issues among states. In some, like Kentucky, the culture is such that kids rarely ever go into court without the early appointment of counsel. Specialized training in Kentucky has long stressed the important differences between children and adults, and the need for zealous advocacy starting with a first appearance, particularly if the youth has been arrested and detained.

In Ohio, where Tandy estimates at least one-third of youth still go through the courts without counsel, the Ohio ACLU and the Office of the Ohio Public Defender filed a request for a rule change with the Ohio Supreme Court that would curb the number of youth who waive their right to counsel, secure legal representation as early as possible, and ensure that no child can waive their right to representation without talking to a lawyer first.

The NJDC recommends the following reforms in order to ensure children’s right to counsel is protected: Deem children automatically eligible for free counsel due to their status as minors, appoint counsel before interrogation begins, abolish fees associated with a public defender, require minors to consult with an attorney before waiving their right to counsel, and ensure that all minors have access to counsel after sentencing. “If [states] undo even one of those barriers,” Scali said, “children in our communities will be able to get lawyers and be able to ensure that they’re not pulled more deeply into a system that we know many of them really shouldn’t be in.”

As is so often the case, children of color and those living in poverty suffer disproportionately from the lacking protections for juvenile’s due-process rights. “We know that low-income children of color are so disproportionately charged for normal teenager behavior that it’s even more important that that these five barriers to access to counsel get broken down,” Scali said. “They need the best protection possible, someone to say, ‘This is not right, we’ve got to stop pulling children in [to the judicial system], arresting their development, and cutting off their future.”

Children, even more so than adults, require meaningful assistance of counsel during legal proceedings in order to ensure their rights are protected and justice prevails. Fortas required all jurisdictions to fully protect these rights 50 years ago when he wrote in the Gault opinion: “[I]t would be extraordinary if our Constitution did not require the procedural regularity and the exercise of care implied in the phrase ‘due process.’ Under our Constitution, the condition of being a boy [or a girl] does not justify a kangaroo court.”

We want to hear what you think about this article. Submit a letter to the editor or write to letters@theatlantic.com.

No comments:

Post a Comment